currently –

reading: memoirs found in a bathtub, a soviet-era genre bending story about a diary found centuries later in a former american military base; a raisin in the sun, lorraine hansberry’s debut play

mentioned: had the opportunity to speak with and be featured in olive pomesty’s piece in the new european about the rise of intellectual content on social media.

viewing: my co-worker natasha during opening night for soonest mended, a play she stars in exploring what happens when a couple opens their marriage.

producing: my first event! bringing together some really incredibly talented and thoughtful people on may 2 to reflect on trump’s first 100 days.

performing: you can hear me read a version of this essay during a storytelling event this tuesday at 6:30 pm at starr bar.

Ever ahead of the curve, long before RFK vowed to “Make America Healthy Again,” my mom was buying organic.

The only cookies in our house most of the time were Newman’s Own, and apparently packing this faux Oreo also made me an Oreo - black on the outside, white on the inside. As if avoiding highly processed foods was something only white people did.

There is a certain type of pain, a silent suffocation of the soul, that occurs while growing up Black in a predominately white suburb. On the one hand, I knew that I was supposed to feel lucky. Everyone from well-meaning teachers to jaded family members often repeated this to me over and over and over. I am here and I am lucky. But I was also told - in so many different ways - that I was different.

Every time I picked up a book or opened my mouth, I went against people’s preconceived notions and stereotypes of what it meant to be Black in America. But because this was America in the early 2000s, people’s backhanded observations were more covert than saying, “Wow, that nigger can read.” Instead, it came in a subtler, more conciliatory tone, though its impact was doubly cruel, a put-down disguised as a compliment.

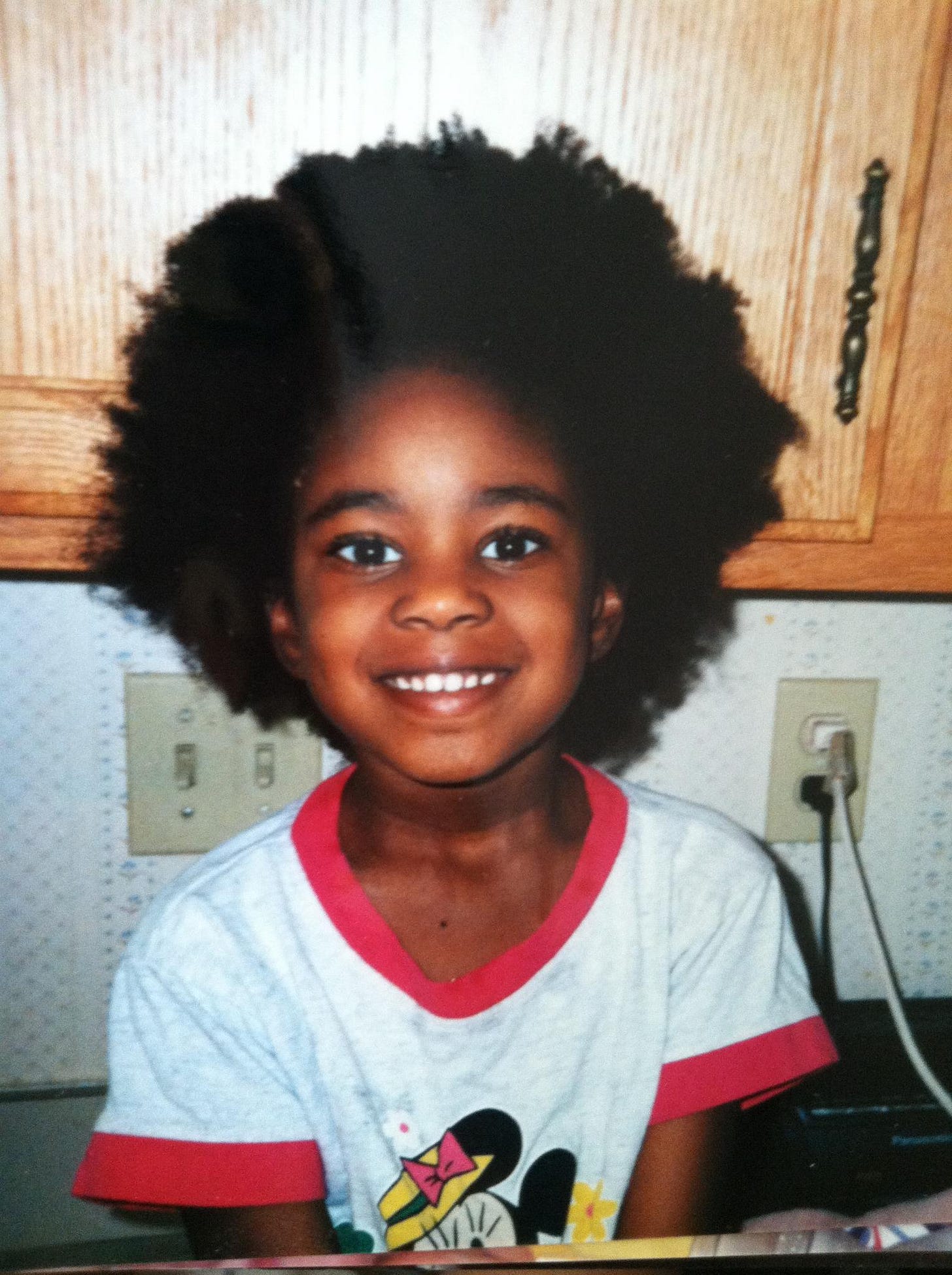

There were earlier examples of this - I was one of only four non-white students in my entire elementary school in Ohio before my family moved to Texas - but one of the earliest memories happened when I was eight or nine in a doctor’s office. Having two younger siblings often meant that all three of us were dragged around to each other’s various appointments, practices, or recitals. Since I wasn’t sick that day, I sat in the extra chair in the examination room, reading a book, while my mother talked with either the nurse or doctor. At a certain point, they looked over at me.

“You’re sitting over there so quietly. What are you reading?” The nurse/doctor asked. She was a white woman with a pinched nose and blank eyes.

“Jane Eyre,” I replied, barely looking up.

“Wow, that’s so advanced! And you understand what you’re reading?”

My mom jumped in. “Kayla is reading at an eighth-grade level now. She just flies through books.”

“Still, though…I don’t even think I could read Jane Eyre!” She turned to me again. “And yet here you are, reading it. We truly live in such interesting times.”

I returned to reading, but an uneasy feeling rose in my stomach. Something about her tone suddenly made me feel self-conscious, as if I was doing something I shouldn’t. It wasn’t anything she said explicitly, but the message I took away from that interaction - and others like it - was that there was something about me simply living my life that made white people uncomfortable.

Nearly twenty years later, I saw this dynamic of low-grade racism in the latest season of Apple TV’s hit sci-fi thriller, Severance.

The show follows a group of office workers at Lumon, a biotech company that has pioneered a procedure called “severance.” People who are “severed” effectively have two personalities: an “innie,” who trudges through the monotony of pushing paper and forced team building while at work, and an “outie” who gets to enjoy life outside of the office. Innies and outies don’t have memories of the other's lives.

Most of the drama plays out between Adam Scott’s character, Mark Scout, a former professor mourning the death of his wife. He works with a trio of other innies who have varying motives and backstories for why they underwent severance. However, my favorites are the show’s side characters: Mark’s bloviating self-help guru brother-in-law; a teenage middle manager who seems like a misplaced extra from Wes Anderson’s “Moonrise Kingdom” as she marches down the hallways in her knee-high socks; and, of course, Mr. Milchick. Seth Milchick, portrayed by Tramell Tillman, is the floor manager who oversees Mark’s “mysterious and important” work and - in addition to Patricia Arquett’s Ms. Cobel - one of the main antagonists for the innie workers.

** very light severance spoilers ahead but major plot points aren’t revealed **

Already a favorite after the joyfully absurd defiant jazz music dance experience, his character received slightly more screen time this season to briefly explore what it means to work in a predominantly white environment. Midway through this season, Milchick is written up for using “big words” and is reprimanded by his white supervisor, the imposing Mr. Drummond. He must simplify his language. Milchick spends time looking at himself in the mirror, practicing shorter sentences, yet Tillman’s portrayal in this scene communicates a deeper inner battle. Milchick’s character development throughout the season touches on this struggle.

Do you change your personality to make others more comfortable and maintain the status quo or remain true to yourself?

There’s a scene early in the second season where a conversation subtly teases this question. Milchick runs into the delightfully eerie Natalie, who has the ominous distinction of “communicating” with the Board. After a promotion, Milchick receives a blackface portrait of the company’s founder, on behalf of the board, from Natalie. This bizarre gift is so he can ‘see himself’ in the work and Lumon’s mission. Milchick wordlessly stares at this portrait before ultimately placing it out of sight on a top shelf in a storage room. When he finally sees Natalie again, he tries to gauge her reactions or thoughts on what she felt when given the same portrait. Natalie instead changes the subject.

Over the last century, different identity groups have developed informal ways to protect one another in the workplace. For women, that might mean subtly letting the new girl know to avoid a particularly handsy executive or that a manager likes to take credit for a woman’s idea. There are similar unspoken norms and rules as a Black person navigating corporate culture. You share if a manager is quietly racist. You trauma bond over drinks about how a white coworker mistook you for the only other Black woman in your division.

By not engaging in the conversation, Natalie communicates that she sees herself first as an extension of the corporation, not as a fellow Black employee trying to make sense of how crazy it is to receive a blackface portrait. She chooses to align herself with the white status quo. Yet as much as Milchick attempts to fight back by choosing to communicate in a way that feels authentic to him, by the season finale we are also reminded that there are still limits. In many ways, both of the show’s Black characters would likely earn the label of “Oreo” as well.

Growing up, being called an Oreo versus something more explicitly racist honestly felt more damaging.

Coming of age during the 2000s meant nothing could capture the angst, the confusion, the complete and utter self-loathing of being a teenager in the suburbs more than midwestern emo and pop punk bands. If it had four skinny white dudes in it, I was likely crying in my room about how unfair life was while listening to their music and writing near novel-length fanfiction about them.

That wasn’t to say I didn’t listen to music written and performed by Black artists - during Limewire’s heyday, I was illegally downloading deep cuts, like Fingertips, to fuel my Stevie Wonder obsession - but nothing quite reflected my middle school journal entries like “I got troubled thoughts and the self-esteem to match.” Unfortunately, people weren’t able to reconcile my love for both 1970s soul and 2000s indie rock. Any interest in white culture or in doing “white people” things, like reading a 19th-century novel in elementary school, was viewed as some hidden desire to want to be white.

At least with the n-word, it’s clear where you stand with the person. But being called an Oreo does two things: if it’s a white person saying it, the term is meant to be taken as a compliment; uttered by another Black person and it’s an insult. Yet regardless of who says it, both instances erase your identity. It’s saying, that by being Black yet liking or acting a certain way, those attributes couldn’t possibly be associated with a Black person, so you must be white - at least on the inside.

To grow up in the suburbs is to straddle these two worlds, looking out and seeing your white peers move with a level of ease you could only imagine while also looking back and seeing that your people are still oppressed. It is having the privilege of only reading about the criminal-legal system yet continually living in fear that all it takes is my younger brother having just one wrong interaction with the police to change that.

Over a century ago, W. E.B. Du Bois wrote about how some try - and fail - to please white, mainstream audiences while simultaneously alienating the Black community. In the Souls of Black Folks, Du Bois refers to this as double-consciousness, “this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity.” It’s this concept that Black Americans are continually trying to figure out our place in a society we didn’t ask to be a part of - and continually doesn’t want us to fully participate in - while also trying to make the most out of this great American ‘experiment’ in democracy.

Some remain adamant in their refusal to assimilate into the mainstream, but as Black Americans have broken barriers in sports, entertainment, politics, and corporate America, there’s still this tension: how much of our identity do we get to retain by achieving these monumental wins? What is gained versus lost in our attempts to be recognized not as three-fifths of a person, but fully human? And that’s not to even touch on the classism within the Black community once you’ve “made” it. As someone from a working-class background - who was only in the suburbs because of some questionable financial decisions my father made that temporarily elevated our economic status - and is now in spaces with Black Americans who vacation in Martha’s Vineyard or have generational membership in Jack and Jill, it can often feel like existing on an island within an island.

Severance isn’t the only story that asks some of these questions - nor is this a major question within the show. What I find so fascinating is that in a mainstream show involving baby goats, deeply meditative philosophical questions, and a love triangle a surface-level exploration of the Black experience in corporate culture was even considered, let alone given screen time. And it also raises new questions. Who gets to tell our stories? In what way are they told? What does our current sociopolitical moment mean for this next generation of Black Americans - those who came of age in a world with a Black president, greater cultural visibility, and improved economic mobility - yet still live under the constant threat of white supremacy?

For most of my life, trying to figure out my place in the world as a Black American who grew up in the suburbs meant I was constantly changing who I was to make others feel more comfortable rather than focus on simply being Kayla. I felt like no matter who I was, I would always be treated with either skepticism - is she really Black - or as a toy to be paraded out when it was politically convenient - look, I have a Black friend - only to be shoved back in the closet until the next social movement deemed me necessary.

After spending the last two decades trying to defend my Black identity, yet feeling like I was constantly failing some test, last year I finally decided I would stop driving myself sick with anxiety in my attempts to prove how people’s perceptions about me are wrong - that there isn’t one thing that makes me any more or less Black, that I am simply because I am.

In the end, I decided my soul might have been wounded trying to navigate these two worlds, but I am still here. I am still here and I am still lucky, and I owe it to myself to find out who I really am: someone who is silly, curious, slightly neurotic; someone who can dissect both Vampire Weekend lyrics and James Baldwin in the same conversation; someone who can fry chicken by sight and prefers vanilla ice cream with a drizzle of olive oil and flaky sea salt; someone who is proud to “bring the gifts that my ancestors gave, I am the dream and the hope of the slave.”

I am me. I am Kayla.

That’s all I’ve ever wanted to be.

And now I get to be just that.

Just me.

you can hear me read a version of this essay during a storytelling event this tuesday at 6:30 pm at starr bar.

Relate TOO hard. Why can't they just let black girls live laugh love

damn. this is a perspective i knew nothing about. thanks for posting this.