seinfeld, a reflection: part ii

This month I’m reflecting on my first time watching Seinfeld last fall. Today, it’s all about the writing and how everyday experiences made their way into the show.

You might be asking yourself, “Why are you spending so much time talking about this show that ended nearly 30 years ago?”

To which I would answer, “Fair question.”

However, I’d argue that no other show since its finale has continued to have as much of an impact on pop culture as Seinfeld. Among other things, it helped set the precedent that TV could have unlikable, kind of terrible characters that would pave the way for the anti-hero. Seinfeld continues to inspire another generation of writers and comedians, many of whom were barely conscious or weren’t even alive in 1997.

I know it’s already inspired me, in large part because it made me curious about television writing and production. Last week I mentioned that the costuming initially captured my heart, but today I want to spend some time talking about the actual substance - the writing.

Note: all quotes and most research going forward, unless directly linked, are taken from Jennifer Keishin Armstrong’s extensive look at the show, “Seinfeldia.” Also, in case it wasn’t obvious, there will be (mild) spoilers.

SHOW DEVELOPMENT + WRITERS

People like to joke that Seinfeld is a show about nothing, but the original pitch was about how a comedian sources his material. In the late 1980s, Jerry Seinfeld wasn’t a household name yet, but he’d had a string of guest appearances on late-night television and short-lived roles on a few shows. It was enough to where people in the industry knew of and respected him, which is why in the fall of 1988, an NBC executive contacted him to see if he was interested in developing a show.

It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. The only problem was that Jerry didn’t know what to pitch. Rather than focus inward, Jerry recognized he needed a collaborator, someone who understood his sense of humor but also had experience writing and producing for television. That person, of course, was Larry David, and the show’s origins would later find their way into the meta-hyper-fictionalized storyline in season four.

Writing for the show was like “being an idea factory - specifically, turning your own life experiences into pitches, and using your life as a laboratory for possible pitches, and listening to other people’s life stories so that you could turn them into pitches.” Taken from this perspective, the show is infinitely more enjoyable because you can see how an everyday experience is tweaked, fictionalized, and/or modified to fit a sitcom format but with that signature Seinfeld twist.

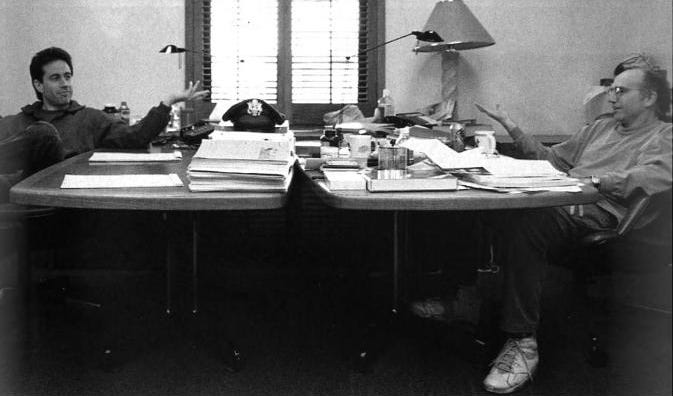

While learning about Seinfeld, I was particularly struck by the fact that the writing process was both collaborative, yet siloed. Writers on the show generated the ideas, sometimes alone, sometimes in writing pairs, but the final revisions and significant edits largely happened behind closed doors - and at two pushed-together desks - by David and Seinfeld. David, in particular, was hard to please - “if the pitch didn’t sound real, [he] didn’t want it” - and his quest for perfection often meant that sometimes sets for a scene weren’t constructed until the last minute because they were written the night before.

Bill Masters ran across a Trivial Pursuit typo. That eventually became ‘the moops’ instead of ‘moors’ in “The Bubble Boy.” Dan O’Keefe’s obscure, slightly embarrassing family tradition was forever memorialized as Festivus. Lorne Michaels’ odd dancing during Saturday Night Live after-parties became Spike Feresten’s inspiration for Elaine’s odd dancing in “The Little Kicks.” Peter Mehlman, who wrote some of the show’s most iconic episodes and scenes - from the “double dip” to Elaine’s signature ‘get out’ push - originally had a background in feature writing and regularly mined his own life for stories.

One of my favorite quotes about the show’s writing process comes from Mehlman as he reflected on developing “The Betrayal,” or ‘the backwards episode.’

I called David [Mandel, who went on to become the showrunner for Veep] because whenever I was working on something, I always came up with small ideas, and I always went to David when I wanted to go to a bigger place.

I keep returning to this quote because it speaks to how the show was both about individual ideas and stories, but also how the writers could work together in order to punch up, tease out, or refine that idea. As I think about my own storytelling ambitions, I’d like to find collaborators who can help me expand my initial concepts into something wonderful.

Unfortunately, like much of the industry at the time, Seinfeld’s writing staff was almost entirely all men. One of the exceptions was Carol Leifer, a New York comedian who was friends with David and Seinfeld in the 1980s and served as the initial inspiration for Elaine. Leifer is behind some of my favorite episodes, including “The Beard” and “The Rye.” She also collaborated with Mehlman (“The Hamptons”) and another female writer, Marjorie Gross.

While the world never got to truly appreciate the full scope of Gross’ talent - she died of ovarian cancer at 40 - her humor is immortalized in episodes like “The Fusilli Jerry.” Leifer would go on to star in her own show, Alright Already, and write throughout the next two decades for awards shows, as well as an episode of Modern Family and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

I’ll talk more about the legacy of Seinfeld, including what other shows writers would go on to produce or write for, next week.

ANATOMY OF A SEINFELD EPISODE

Cold Open

In earlier seasons, the cold open was Jerry in some dark comedy club performing one to three bits. Often, but not always, these bits had a connection to either the episode title or a joke later on in the episode. As the show progressed, this format was later replaced with a more conventional sitcom opening featuring a brief conversation - sometimes nonsequiturs, other times teasing the plot ahead - between two or more of the principal characters.

The Set-up (first 1-3 scenes): Introduces the plot, major conflict, and set-up jokes or future gags.

These first scenes - usually at Monk’s or Jerry’s apartment - help establish the setting, especially if it’s an episode where the cast is venturing out of the Upper East Side. It’s also where the main conflict is introduced or we receive a hint about the eventual conclusion.

For example, in “The Hamptons,” the initial scenes have the characters driving to establish where the rest of the episode will take place and why they’re not in their typical location. They’re off to see a friend’s new baby. We also learn that George still hasn’t slept with his girlfriend - who will be joining the group - and his love of Hampton tomatoes. Each of these pieces of dialogue is set up for future jokes and the eventual conclusion.

The Release (majority of the episode): Our characters are thrust from their starting point and have to interact with the world.

After the plot and jokes are established, Seinfeld needs to place its characters in situations that highlight the show’s signature observational humor and continue to advance the plot.

In “The Hamptons,” the rest of the gang sees George’s girlfriend as she sunbathes - topless - which sets up a series of escalating jokes and bits. Even the insecure, immature man child that he is, George tries to come up with different ways to see Jerry’s girlfriend, Rachel, naked. Of course, this is gross, and of course, this spectacularly fails. She walks in on him - right after some “shrinkage” has occurred after a dip in the pool.

Minor sub-plots, like Elaine trying to figure out if the pediatrician visiting the (ugly) baby is into her, or Kramer randomly finding a cage full of lobsters, are also introduced.

Converge (final 1-3 scenes): Whatever the main problem/tension/joke that was introduced finds its resolution.

Larry David is obsessed with converging storylines. You can see this even more in Curb Your Enthusiasm, but it all began on Seinfeld. At the end of “The Hamptons,” Elaine finds out the pediatrician wasn’t into her and Kramer gets arrested (those lobsters he found were part of a commercial farm). And George, who never did get to see his girlfriend al fresco, finally gets his beloved tomatoes - through a car window and to the face, courtesy of Jerry’s girlfriend, whom George tricked into eating lobster.

Closer (credits)

Mirroring the start of the episode, this is either another stand-up set (if it’s an earlier season) or an extension of the final joke.

WHAT MAKES A GOOD EPISODE?

I thought it would be harder to pick my ten favorite episodes, especially since there are so many to choose from, but a good Seinfeld episode for me ultimately needed to fulfill two things:

Each of the four characters has to have a strong, distinct story or conflict they are trying to overcome.

After a table read for “The Pen,” the only episode that doesn’t feature George, Jason Alexander pulled Larry David aside, “If you write me out again, do it permanently.” There are still some episodes I enjoy that only focus on one or two characters. However, I’m glad Jason made this comment early on because I think Seinfeld is at its best when each of the principal actors has enough material and scenes that not only show their skills but also how well they interact with each other.

I need to laugh so hard I’m crying.

Look, I get it, it’s a sitcom. I’m going to laugh. But not every episode can be a hit. There were many episodes - particularly in the earlier seasons, but also the first half of season seven - where I kept waiting and waiting and waiting to laugh only to eke out a tiny ‘ha’ here or there.

My favorite ten episodes are the ones that had me in stitches, the ones that made me sputter and nearly choke and cringe at their absurdity. They are the episodes where, on first viewing, I knew I would find myself returning to again and again. These are…

MY FAVORITE SEINFELD EPISODES

1. The Pothole (S8 E16)

If you want to understand the anatomy of a Seinfeld episode, this is my go-to. Each of the characters has absurd storylines - Jerry knocks his girlfriend’s toothbrush in the toilet, Elaine is trying to have Chinese food delivered, Kramer adopts a highway, and George loses his keys in a pothole - and the way they finally converge with a charbroiled Newman screaming “oh, the humanity!” always leaves me in tears. Perhaps my favorite part about this episode is the pacing and quick cuts of this episode - whether it’s a shot of George with a jackhammer while Elaine hauls carpets in the background, or the Phil Rizzuto keychain flying in the air after it’s dislodged. And you can’t go wrong with Kristin Davis, who guest stars as Jerry’s hot toilet toothbrush girlfriend.

2. The Merv Griffin Show (S9 E6)

This episode is pure, unhinged chaos. Kramer finds the set of the Merv Griffin Show (despite it ending years ago, but that’s TV magic for you) and Jerry will go to any length to play with his girlfriend’s toys. In typical George fashion, he disappoints yet another woman - this time by running over all sorts of New York City wildlife - and we’re reminded that Elaine has a job with the Sidler, a guy who always sneaks up on you. This episode has some fantastic one-liners - El Paso, I spent a month there one night - and was clearly an inspiration for Adult Swim-era comedians in the 2000s. This is Eric Andre’s favorite Seinfeld episode for a reason.

3. The Contest (S4 E10)

Proof that you don’t need a TV-MA rating to talk about sex and do it in such a way that is both hilarious yet still cringe-inducing. I don’t need to recap this episode, in part because it’s the episode almost everyone knows - are you still the master of your domain? - but what I will say is I love that Elaine is included in the bet and that she was one of the first to lose - after Kramer, of course. This episode also reminded me that I should probably get blinds…

4. The Hamptons (S5 E20)

The gang leaves the Upper West Side for the Hamptons where they discover shrinkage, a horrifically ugly baby, and eat illicit lobsters. Plus, how can you not love Kramer’s delightful Beach Boys montage?

5. The Chinese Restaurant (S2 E 11)

The best early-season episode, though it didn’t make the top three since the show is still finding its footing. It’s a special episode because you can see what the show will evolve into. In the earlier seasons, Jason was playing George more like a Woody Allen-type, which comes out in this episode. Julia’s facial expressions, particularly when she goes up to the table to ask for food because she’s so hangry, are incredible. I could easily see her bet as a Broad City episode. Jerry has a sister who is never mentioned again, though I do think that might have been a missed opportunity - both for jokes but also in terms of casting. Janeane Garofalo would have been perfect as his sister instead of his random fiance at the end of season seven.

6. Junior Mint (S4 E19)

“Who are you to play God?”

This is a classic season four episode: it’s got the one-liners, a larger-than-life story, visual gags, and a subplot that only George could find himself in.

7. The Mango (S5 E 1)

This is arguably the strongest season opener, especially coming off of the heights of season four. This episode is incredibly raunchy for primetime television, but where Friends couldn’t even show a condom wrapper, Seinfeld could get away with talking about how Elaine never had an orgasm with Jerry, and George solves his temporary ED with mangoes.

8. The Parking Garage (S3 E6)

Another example of how an everyday experience - forgetting where you parked your car - takes on a Seinfedlain approach.

9. The Fusilli Jerry (S6 E 20)

Another example of the classic Seinfeld episode. Everything about how it ends is expertly foreshadowed, but you still can’t believe it went there - corkscrew pasta and all.

10. The Betrayal (S9 E 8)

Near the end of the show’s run, it was clear they were running out of ideas, but that also allowed the show to explore different types of storytelling. While other episodes make me laugh more, I love how Seinfeld trusted its audience enough to try something different - tell a story in reverse - and how it adapted one type of source material, a Harold Pinter play.

In my final post next Sunday, I’m talking about Seinfeld’s cultural significance - both as it was airing but also how it continues to inspire comedy three decades later. I’ll also unpack some of the ways the show hasn’t aged well, including how it handled race, sexuality, and gender.

Until then!

xx Kayla