"waiting for a new people"

a look at lorraine hansberry's life and the absence of political involvement in today's mainstream culture.

currently —

reading: rattlebone, a coming-of-age novel set in 1950s kansas, and clean, a chilean domestic thriller

watching: yellowjackets + living single

eating: saraghina’s granola - typically sells out the day of but if you happen to snag a bag, it’s become one of my favorite breakfast toppings

listening: kelela’s in the blue light after @lovie.world’s recent recommendation

“We are waiting for a new people.”

Jean Toomer, Brown River, Smile

Over the last week or so, I have quietly fallen in love.

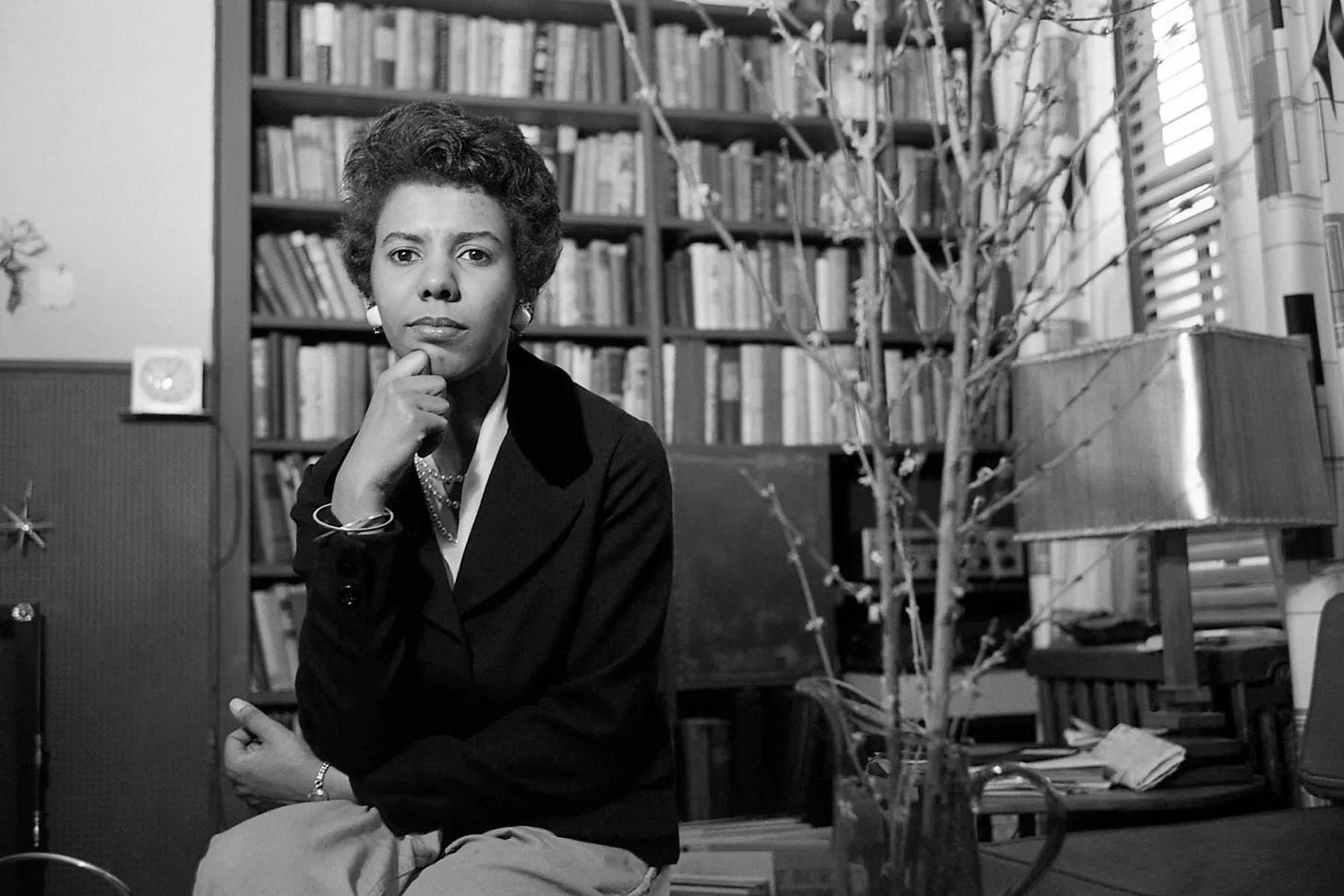

Lorraine Hansberry is an artist that has, until recently, remained at the periphery of my awareness, a fact to recall during moments of random trivia - the first Black woman to have a play, A Raisin in the Sun, produced on Broadway. I have a faint memory of reading it when I was in high school, but when press for Imani Perry’s newest release started making the rounds, something told me I first had to start with her brief sketch into Lorriane from 2018. The book couldn’t have come to me at a better time.

Lorraine grew up in an upper-middle-class home in Chicago’s South Side. Her father was a landlord, renting out kitchenette apartments that would eventually become the setting of Lorriane’s most famous work. Much of Raisin contains autobiographical references. As a child, Lorraine’s family moved into a white-only neighborhood that became the site of racial violence - a brick thrown by an angry white mob just barely missed her head - and would eventually become one of the early Supreme Court cases that would challenge housing discrimination in the 1940s. Someone of Lorraine’s background could have done the easy thing: gone off to Howard University, where her uncle taught, or another historically Black institution, met a nice man before having a few kids, perhaps spending her time organizing on the side through the NAACP.

Instead, Lorraine integrated the female dorms of the University of Wisconsin at Madison before spending time at an artist collective in Mexico and completing a time-honored tradition of young twenty-somethings. She moved to New York, though not to Harlem. Instead, Lorraine first made a home amongst 1950s beatniks, communists, and a nascent queer community in Greenwich Village, a neighborhood she would continue to have a presence in throughout the rest of her life. It was there that she met her Jewish husband, began to study under Black intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois, and tried her hand at several creative pursuits - one of which would ultimately become Raisin.

Reading about her wonderfully radiant and radical life during our current political moment has left me wondering: where are our Lorraines?

For a brief window of time, American culture was defined not just by elected political leaders but by an equally impressive group of creative intellectuals, activists, and everyday people who were able to turn a mirror toward both the minutiae of their lives and injustices they faced, documenting their experiences through writing, music, and other art forms.

One of the most striking things about Lorraine - and there is a lot - was her unwavering commitment to radical political involvement. She dabbled in leftist causes throughout her brief life, traveling to South America to speak at a communist conference, publishing political commentary drawing connections between African colonial struggles and the Jim Crow South - enough to earn the scrutiny and surveillance of the FBI. After the runaway success of Raisin, Lorraine was unwilling to let the fame and attention that came with it water down her politics. Even as she was sitting in closed-door meetings with Robert Kennedy, appearing on panels, or hosting fundraisers for the student-led civil rights movement in the South, she always stuck to her beliefs.

Part of why I grow increasingly disillusioned with social media but also the personal essays that tend to dominate this app (and that I have been guilty of writing) is we are now so quick to mine our internal lives without taking a step back to observe, assess, and critique our surroundings.

Content is now made either explicitly or indirectly to serve our desires for instant gratification rather than exploring our relationship and connection to a broader community - virtual or otherwise. Better to remain as middle of the road and moderate as possible for the clicks and views and likes. Better to share fashion hauls than to question the labor that goes into it. Better to write about a bad date in the most surface-level way possible than dig one or two levels deeper about what that means about shifting gender roles in our country or globally. Better to pose as a thought daughter by reading the words of past intellectuals than critique or question issues of today. Better to consume than to nourish, abstain rather than challenge, forever a girl because to grow up would mean to take ownership of the world we live in and the role we play in shaping it.

Right now, while Democrats file legal challenges and provide commentary on cable news, I believe those of us both within and outside the mainstream are missing an opportunity to come together. We are missing an opportunity to create something larger than ourselves by continuing to place all of our hopes on a group of elected officials when history has repeatedly shown us that social movements and change require action at the grassroots level as well.

Democrats are not coming to save us because they have historically favored maintaining the status quo.

Ever since the 2024 election and subsequent inauguration, op-eds and hot takes on social media have seemed to focus on where the Democratic Party is, and why there aren’t more leaders - outside of seemingly AOC and Bernie Sanders - taking a forceful position. Yet this current moderate stance and lukewarm action by the Party is a feature, not a bug. Modern Democrats like to position themselves as the champion of Civil Rights, of progressive values, but this narrative obscures how much of the reforms and legislation we now associate with this party was based on decades of grassroots organizing.

The modern Democratic Party remains vague about its pre-New Deal origins, but directly following the Civil War, the Party had two factions: a vaguely progressive but still quietly racist bloc in the North and the openly racist Southern Democrats who challenged efforts led by “Radical” Republicans during Reconstruction, which they viewed as “Negro dominated.” It was Southern Democrats, not Republicans, who enacted violence and Jim Crow laws; Northern Democrats made the very conscious decision to accept these views for decades to maintain political power at a national level.

In the 1930s, President Roosevelt tried unsuccessfully to reshape the party by supporting candidates in the South who were more closely aligned with his New Deal vision. For the next thirty years, Northern Democrats continued their moderate stance on civil rights and unionization to appease Southern segregationists. Occasionally there were confrontations, like the 1948 “Dixiecrats” splinter group after the party began adopting a more public position around extending civil rights to Black Americans. But part of what is missed in the narrative about the Civil Rights Movement is that there was an inevitable nature to it, either glossing over the amount of violence that occurred before legislation like the Voting Rights Act was signed or ignoring its Cold War context in which segregation was a massive PR problem for America. One can’t exactly promote “democratic” values when a significant portion of the population is politically disenfranchised, living in fear of their homes or places of worship becoming the site of violent bombings, and facing attacks during nonviolent protests.

The same year President Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Democratic National Convention was still segregated.

It took the coordinated action of different groups, particularly, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), to challenge white supremacy within the Democratic Party’s southern states and at the convention. The MFDP was an off-shoot of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), a coalition formed in 1962 that combined the efforts of various organizations - Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Congress of Racial Equality, and the NAACP - who were leading voter education and registration drives in the South. In 1964, a group within COFO ran a parallel delegation process to select delegates for the 1964 Democratic Convention.

During “Freedom Summer,” Black activists made their way to Atlantic City, demanding the party reflect the values it had just passed through legislation. President Johnson, fearing a Southern Democratic walkout - which would destabilize the convention during an already tenuous political environment - tried to get ahead of the breaking story by issuing a press conference to avoid live coverage of Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech, “I Question America.”

LBJ’s move ultimately backfired though. The news ended up reporting Hamer’s speech for days - along with the President’s attempt to suppress it - pushing the Civil Rights movement further than the more moderate, “slower” response mainstream Democrats had initially hoped for. The actions of this group from Mississippi would go on to inspire the “single greatest moment of party reform in American political history,” shaping the influential 1968 and 1972 conventions and fundamentally changing how delegates are selected through the primary process we know today.

While the student movement and grassroots organizing captured the public’s attention, influencers of the time made an effort to promote and support these efforts - either through reporting, financial contributions, or their art. Near the end of her life, Lorraine gathered a group at her upstate house to raise over $5,000. Funds from that event would help pay for a station wagon that was used by activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner - victims of the brutal triple murder known as Mississippi Burning. Their deaths helped draw national support for the eventual passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Change does not happen overnight.

The passage of Civil Rights legislation in the 1960s was part of a nearly-century-long struggle that played out not only through court battles and reinforced by racial violence, but in mutual aid groups, conversations in living rooms, and individuals willing to stand up for their beliefs - sometimes at great cost. People were also in conversation with one another. The work of the MFDP is just one of several examples in which groups outside of the traditional political process were able to effectively leverage the media and technology of their time to keep the public’s attention on issues important to them. Even if those groups didn’t always agree on the means, they were able to work together towards achieving a shared goal: a vibrant and free democracy.

We are currently witnessing a fundamental reshaping of our government and the global order, yet many of us are still operating under a business-as-usual mindset.

Unfortunately, these are not normal times. And I think the sooner we come to terms with this new reality, the better equipped we will become to meet the moment rather than hide behind fear and wish we had done something sooner. It is easy to want to bury our heads in the sand, to keep our focus on what is directly in front of us rather than pop up, see a world that we increasingly do not recognize, and make the conscious choice not to engage because we are too tied or overwhelmed or unsure or just trying to focus on making ends meet.

Those are all valid responses, one I imagine people throughout time have also felt. And yet we have the rights and freedoms we currently have (and are in the process of being stripped away) because people with those same concerns, worries, and weariness also saw something bigger than themselves at stake that was worth committing to. Political activism and involvement don’t always have to mean getting out on the streets and protesting. Lorraine and her creative peers, whether that was other Black intellectuals like James Baldwin or Joan Didion’s earlier work writing profile pieces about leaders of the American Communist Party and capturing other social changes of the era, were all using their talents to capture their present reality to help others around them make sense of it.

Right now we have an opportunity to share, contribute, and shape the conversation about the future we want to live in. I would hate to look back, wishing there was something I could have done, only to come up empty-handed.