seinfeld, a reflection: part iii

Exploring the impact of Seinfeld in today's media. (Spoiler alert: Three Seinfeld writers are to blame for the terrible fever dream that is 2003's Cat in the Hat.)

In our era of streaming and a fractured media culture, it’s hard to appreciate now just how big of a deal Seinfeld was at the time. 30 million Americans, on average, tuned in to watch Jerry, Elaine, George, and Kramer.

When the show announced it was ending, it launched a monthlong media frenzy and the finale drew over 70 million viewers (likely more when considering viewing parties). When we compare this with shows that came in the 2000s, even before streaming took off, these are still big numbers. The scale of the show’s success took NBC from a middling network into its golden era of ‘Must-See TV,’ which it wouldn’t achieve again - and at a much smaller scale - until the late 2000s with shows from Greg Daniels and Tina Fey. At the height of The Office, episodes barely passed the ten million mark, though it now has an extended life in the streaming era (and all those podcasts). A show like 30 Rock was only drawing one to two million viewers, if even.

The show’s massive success translated to ad revenue for the network, which meant that Seinfeld and David had a level of creative control over what they could or couldn’t show on network television - more than perhaps any other series at the time. The fact that there’s an entire episode about masturbating, subplots about George wanting to eat in bed while having sex, or Elaine admitting that Jerry never made her orgasm, might all seem relatively tame by today’s standards but they were pretty risqué for 1990s mainstream content. Even now, Netflix has reclassified the show's rating from its original TV-PG rating to TV-14.

Seinfeld didn’t just introduce more sexuality into television, it also - in a way - introduced American Jewish culture to the masses. While canonically only Jerry is Jewish in the show, all four principal actors have Jewish ancestry. Most of the writers, producers, and other creatives working in the show also came from a Jewish American background. This Jewishness initially made the network nervous - coastal elites might watch the show but would Middle America? Yet the shows found an audience anyway. It found that audience not by explicitly focusing on Jewish culture but through its larger observations that often had a Jewish lens. An episode like “The Rye” could probably still work with Brioche, but the set-up and eventual payoff in a later episode at a Florida senior community adds to the humor. Bryan Cranston’s character, Tim Whatley, was a Penthouse reading, re-gifting dentist who eventually converted to Judaism ‘for the jokes.’

There is also an entire language of Seinfeld that permeated throughout American culture. Without even seeing the show, I regularly bemoaned double dippers and would throw in a “yada yada yada” at the end of conversations because their usefulness, their meaning, was learned or implied through growing up in the late 90s and 2000s. To me, that is the ultimate legacy of the show, the fact that people who might not know the nuances of Seinfeld are still engaging with and recontextualizing its content.

Of course, that doesn’t mean the show was perfect.

Criticisms

Alright, let’s finally address the elephant in the room: the show’s lack of diversity.

I have mixed feelings on this. On the one hand, the representation of minority characters was often questionable at best and highly problematic at its worst, like with Babu Bhatt’s storyline. However, the world in which the show’s characters exist - the Upper West Side - is fairly white, Jewish, and middle to upper-middle class. While we all like to believe we live in a post-racial society (maybe not as much now, but we were drinking that Kool-Aid in the 90s) the fact remains that people across all demographic groups tend to socialize more with individuals within their racial group, even more so for white Americans.

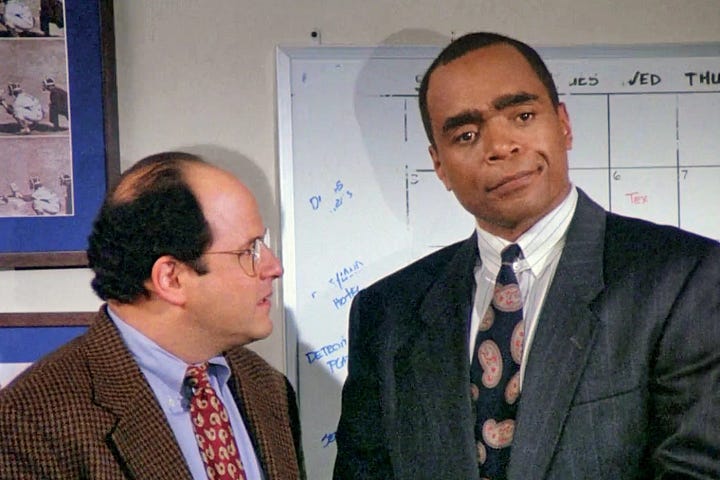

And as Lauren Michele Jackson points out in her aptly titled Vulture essay, “When Black People Appear on Seinfeld,” the show did have its fair share of Black characters, even if their role was more ancillary.

…[Black] characters play a significant role precisely because they are true strangers — estranged by city planning and the color line — for these main casts to bump up against. Those frustrated with the sweeping whiteness of shows that presuppose a New York City state of mind — from the mundane (How I Met Your Mother) to the iconic (Girls) — must grant that they are not unlike the way white residents, transplants or not, experience the city, moving alongside and in between darker people whose lives are not worth their curiosity.

The criticisms around race also lack nuance when considering that the 90s was a renaissance for comedy and content geared toward a Black audience. At one point, there were 15 shows on mainstream television with predominately Black casts and actors. It’s not that Black comedy didn’t exist, we were just off doing our own thing on shows like Martin, In Living Color, The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, and Living Single. Perhaps actors felt less of a need to appear on a show like Seinfeld because this was a time when Black voices had a space in other content.

That’s not to excuse the lack of people of color - just because something is doesn’t mean that it should remain that way - but the lack of diversity on the show wasn’t a uniquely Seinfeld problem. NBC’s other, more traditional sitcom, Friends, has virtually no racial minorities, even in guest roles. I do still believe it’s valid to discuss, and it does point to the larger systemic issue about race in the media at that time, which is especially apparent in the episode: The Puerto Rican Day.

Honestly, this episode is disappointing on so many levels, both because this was just a lazily written episode - despite being written by all 10 of the show’s main writers - but more importantly because each of those staff writers felt it was appropriate to show a burning Puerto Rican flag. Why couldn’t it have been the Macy’s Thanksgiving Parade or another nuisance that prevented the gang from getting home? While I understand it was not intentional in the show’s universe - instead it’s played off as part of a “comedic” accident - it speaks to the lack of diversity within the writer’s room and across the network. When it aired, Puerto Rican groups rightfully protested for weeks and the episode was, at one point, pulled from syndication, before quietly making its way back on air in the early 2000s.

Television Today

During my research for this final essay, I was struck by how much the show had both a direct and indirect influence.

There’s the obvious, like Curb Your Enthusiasm, which I would argue is just an extension of Seinfeld but with a TV-MA rating and if George - whose storylines were often pulled from Larry David’s life - was the main character. Many of Seinfeld’s writers, producers, and directors have lent their creative talent to Curb over the years. Creators of my favorite shows of the last decade have cited Seinfeld as a direct influence, but I was also unknowingly absorbing Seinfeldian humor from other writers and contributors who would go on to shape media in the 2000s.

Larry David played an immense role in the development of the show. A writer might pitch and contribute to an idea, but David was known for his heavy revisions that would make their way into the final cut. When David left the show after the seventh season, there were concerns - both from the public, but also internal anxiety amongst the show’s writers and producers - about whether the show could remain as funny as it once was. This is why some fans talk about the post-David seasons in a holier-than-thou tone. It’s not as good.

Although I would agree that when taken as a whole, the last two seasons didn’t have as many strong episodes as, say, the meta heights of season 4, completely writing off the post-David seasons would mean missing gems like “The Blood” or “The Pothole,” my personal favorite.

Part of what I enjoy about those later episodes is the show was forced to innovate, which meant bringing in younger writers and pitching crazier stories. The most direct influence of these later two seasons is from the different writer’s “alliances” that formed (prior to David’s departure, there wasn’t a traditional writer’s room) and how one of those teams would continue to collaborate well into the 2020s.

Mandel-Berg-Schaffer

David Mandel, Alec Berg, and Jeff Schaffer met during their time at Harvard in the early 1990s. Given the enormous popularity of Seinfeld at the time, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that three former Lampoon staffers were able to make their way into the show’s writing room. Some notable episodes out of this collaboration include “The Summer of George” and “The Chicken Roaster” (Berg and Schaffer) but the trio also worked on the first two episodes of the final season (The Butter Shave and The Voice).

However, I inadvertently knew of the trio through The Cat in the Hat. Yes, you read that right - three former Seinfeld writers were behind the fever dream of a screenplay that is currently one of several early 2000s gems Gen Zers are discovering, recontextualizing, and memeing.

They also co-wrote Euro Trip, which bombed at the box office but became a cult classic among straight Millennial men I know from Austin to Vancouver to Brooklyn. Three male friends are going on a European boy’s trip this summer and have (jokingly?) referred to it as their Euro Trip. Neither of these two films are that great - sorry - but this group would continue to refine their humor in the later half of the 2000s on movies like Bruno and The Dictator, both of which I saw in high school and would continue to influence the humor of suburban boys the world over.

Thankfully their comedy has evolved and matured over the last ten years - less sex and potty humor and more refined middle-aged dad.

Mandel was a producer on Veep, once again collaborating with Julia Louis-Dreyfus, and would eventually become the series showrunner after creator Armando Iannucci’s departure. Berg also found success on HBO, directing and executive producing Silicon Valley before co-creating Barry with Bill Hader. Schaffer created and produced The League, an FX show starring Nick Kroll and Mark Duplass - among others - that largely flew under the radar during its run (or at least it never captured my attention, despite basically subsisting on FX and FXX content through the first half of the 2010s).

Other Notable Writers

Jennifer Crittenden, one of the few female writers on staff, also wrote for the Simpson and would go on to serve as a creative consultant on Arrested Development while producing Everyone Loves Raymond. Crittenden would later reunite with Seinfeld alum Julia and director Andy Ackerman for The New Adventures of Old Christine.

I would argue that if the 90s were defined by Seinfeld and Larry David’s oddball humor, the 2000s was the Greg Daniels era. Daniels wrote a season three episode (The Parking Space) before joining Saturday Night Live and going on to create, co-create, write, and/or produce shows that would define Millennial humor - King of the Hill, The Office, Parks and Recreation. One other honorable mention for someone with a one-episode credit designation is Peter Farrelly, who gave the world stoner hits like Dumb and Dumber and Me, Myself, and Irene.

Rise of Observational Humor + Millennial Comedy

In the 2000s, shows shifted back to a more traditional sitcom format with relationships and drama and actions having consequences. There were outliers and innovations, especially in the rise of mockumentary that began with shows like Arrested Development and The Office (UK). 30 Rock gave us even quicker cuts, visual gags, and outlandish stories. But these were shows created by an older generation, Seinfeld and David’s peers.

While Seinfeld can’t take credit for creating observational humor, its wild success while airing, as well as its continued life through syndication and streaming, meant that audiences became comfortable with this style of comedy writing. In many ways, this is the other lasting legacy of the show - shifting comedy from traditional jokes to mining our own lives for stories to tell. We see this in the generation of comedians who grew up with Seinfeld. What is Millennial humor if not the deeply personal and often plotless? The point about Seinfeld, more than any other show at the time, was that you were tuning in for the jokes, for the unpredictability of it all.

It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia following another quartet of even more deranged and unlikable characters is the most obvious heir apparent. There’s also Broad City, a personal favorite, which is what I’d like to imagine if Seinfeld were focused more on Elaine, but there are others if you look closer.

Late 2000s and 2010s Adult Swim content draws heavy inspiration from both stoner culture and late 80s/90s media, including, among other things, Seinfeld - especially the later seasons. As I mentioned in my last post, Eric Andre used “The Merv Griffin Show” as a direct influence for his style of uncomfortable, chaotic celebrity interviews. Episodes like “The Serenity Now” or “The Blood” also have an odd, uncanny tone to them that - given some directorial changes and a more mature content rating - could easily find themselves as a 10-minute fever dream short airing at midnight.

Final Thoughts

I started this “Month of Seinfeld” by talking about how I had fallen in love. Spending the last few weeks reflecting and doing additional research on the show has only made that love stronger. This show is by no means perfect, but it was the catalyst for taking me on a journey that is now all about focusing on larger creative pursuits.

And for that, I will forever be thankful.