Everything seems coated in a thin veneer of nostalgia lately.

There are the obvious signs, the seemingly endless march of biopics and period pieces that often oscillate between either nineteenth-century Britain, the mythical American West, or the forty-year window that marks World War II and the early 1980s. College-educated millennials still seem stuck in their mid-century modern decor phase, trading West Elm for upscale vintage pieces as their incomes slowly rise. Scroll through social media and you can find people (often women) showing off either the clothes they’ve made or entire homes they’ve filled with collected pieces from the decade of their choosing.

It’s like one day we all woke up and decided we weren’t going any further, that cultural innovation had accumulated to a certain point and now we can simply recycle it all. Recycle the clothing, either through thrifting or fast fashion hybrid dupes. Recycle the media, through reboots and IP. Recycle the decor. Recycle the politics.

To be fair, that’s not to say the last twenty years haven’t seen any innovation. Yet it’s also hard to deny that life increasingly feels like we’re all looking through the rearview mirror, clinging to the past instead of collectively imagining a future. In other words, we’re all nostalgic.

WHAT IS NOSTALGIA?

Nostalgia’s meaning has evolved over the centuries. The term was first recorded in the late sixteenth century by Johannes Hofer, a Swiss physician. He was at a loss for how to capture a distinct set of emotions - obsessive thinking about home, crying, anxiety, insomnia - that Swiss soldiers experienced while abroad. Hofer combined two Greek words - nostos (return) and algos (pain) - to define this new medical condition caused by “the suffering evoked by the desire to return to one’s place of origin.” Doctors would classify nostalgia as a neurological disorder until the late nineteenth century.

During the early days of modern psychology, nostalgia was used to describe a form of depression people experienced due to the mass displacement of people, either immigration or - beginning in the early twentieth century - modern warfare. For the next hundred years, this type of nostalgia was captured by several terms, ranging from “immigrant psychosis” to “mentally repressive compulsive disorder.” However, while nostalgia went through different iterations, the connection to home, to “the pain which the sick person feels because he is not in his native land, or fears never to see it again,” remained constant. This began to change, though, by the late 20th century and it’s in this new, contemporary meaning that nostalgia becomes harder to define because it can now exist on several levels.

Individual and interpersonal nostalgia are often the two forms we think of. At the individual level, you feel nostalgic about memories that are specific to you. It’s the smell of your mother’s shampoo or how it felt to sit under a certain tree in your backyard. Interpersonal nostalgia focuses on shared cultural experiences, though that can also exist in a few different ways. There are the family memories and bonds you might have. Maybe you’re spending the holidays with loved ones exchanging stories and reminiscing about old times.

Interpersonal nostalgia can also exist in a larger group, like your graduating class in high school or even an entire generation. Mentioning a specific television show or game that you enjoyed growing up can easily function as a low-stakes bonding activity.

Our modern understanding of nostalgia often requires an active selection of what to remember. This allows us to cherry-pick parts of our memory rather than confront the full range of the experience. Earlier this week I spent part of the holiday driving around the suburbs of North Texas. I couldn’t help but focus on positive memories and associations, even though many of the places I drove past were the sites of physical or psychological trauma.

We do a similar type of deletion or revision of history on a societal level. Memory and what we choose to remember (or forget) can help uphold a specific ideology or status quo. Part of why “Make America Great Again” is so powerful is that those four words capture a fictionalized past at both the personal and societal levels. All without having to confront the decades of policies - and the people behind them - that contributed to this sense that something is lost.

It’s easy to picture this idealized, Leave it to Beaver world, deciding to hold all of the “good” (America at the height of its power and influence, a period where the middle class thrived) while also skimming over the “bad” (the fact that this abundance was only accessible to a relatively limited segment of the population).

This type of nostalgia is not new. The Renaissance was a period of revisiting ancient history. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth century saw a return to the pastoral. However, what makes those previous eras of reminiscing different is that our current version is a collapsed, individualistic retrospective rather than a larger, societal one.Nostalgia is no longer confined to a cyclical nature defined by larger cultural movements and trends but instead unrestrained, lending a rather chaotic energy to how we think about and process the past.

Nostalgia is now less about feelings for a specific place and more about memories of a specific time.

This shift makes it easier for us to try and capture perceived feelings of what it might have felt to live “back then” by buying things. As we experience more climate-related disasters, rising income inequality, and all of the wonderful things about what it means to live in the twenty-first century, there is something seductive - but also therapeutic - about turning inward, turning to the past for comfort.

Now we no longer yearn for our childhood suburban streets, but instead, the safety and stability (perceived or real) that we can only attain now through consumption. In other words…

THANKS, CAPITALISM

To understand why nostalgia has transitioned from a physical place to focus so much not just on time but the consumption of goods from a particular time, we need to take a little detour into modern philosophy.

Over the last two hundred years, beginning with the Industrial Revolution and accelerating during our modern “information” age, Western society and culture have gone from one grounded in reality to the abstract. Capitalism requires what Martin Heidegger refers to as the “withdrawal of being,” placing a greater emphasis on a person’s contribution to the market rather than taking pleasure in simply existing. A person’s value is no longer what they contribute to their community, the God they pray to, or the monarchy they serve, but to furthering the expansion of capital.

When Western society began to transition from an economy built on raw goods to one defined by information, philosophers of the midcentury took this idea of withdrawal a step further. Modern capitalism now prefers quantitative over qualitative data. It is easier to decide what plants to close or where to locate toxic waste sites when those decisions no longer center around a person’s humanity but instead on what an algorithm says will result in the highest returns and yields.

Today’s interdisciplinary thought puts greater focus on science over experience, hence the recent focus over the last few decades on STEM. The acronym was first introduced in 2001 by the National Science Foundation to focus education around science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. Our society was training young minds for the future ahead at the expense of the humanities. The fact that liberal arts were tossed in to create STEAM over a decade later points to the low priority our modern institutions place on the arts and qualitative experiences.1

Our modern society no longer values qualitative aspects of living, like the time and energy an artist puts into creating something. Instead, we only view the end product as more data to consume, binge, or scrap. Anything worthwhile pursuing should have a clearly defined “purpose,” a case that is easier to make for learning how to code than studying something like the politics of smell.

“Lamenting the ‘loss of meaning’ in postmodernity boils down to mourning the fact that knowledge is no longer principally narrative.” - Jean-François Lyotard

We’ve truly lost the plot, trading art - and the humanity that goes into creating it - to instead generate something that vaguely resembles the original image. Life is now a copy without reference. Jean Baudrillard describes this switch in his seminal work, Simulacra and Simulation. In a few generations, we have gone from: 1) images directly reflecting a reality; to 2) masking or obscuring reality; to 3) images masking the absence of reality; and 4) finally having no relation to reality.

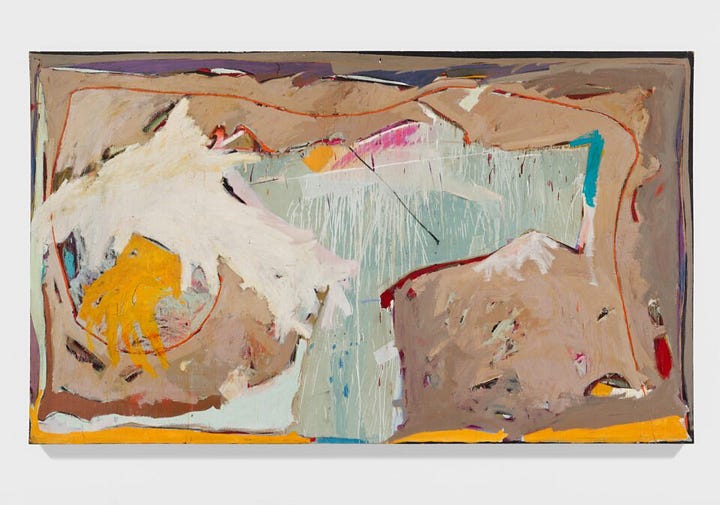

Artists across different mediums, but especially painters, have helped us capture this. Visual art in the early nineteenth century was largely naturalistic, even when depicting more fantastical elements like ancient mythology. The goal was to render the human body and the world as faithfully as possible. Yet by the end of the century, popular artists were more concerned with the impression of reality. Various movements in the twentieth century would continue deconstructing the real to the abstract, stripping down reality to its barest symbols until all that’s left is “conceptual.”

Whenever I would hear people refer to modern life as a simulation, my gut reaction was picturing something resembling movies like The Matrix and quickly dismiss it. However, at its core, a simulation is simply an “imitative representation” and it is in that definition that I’ve finally come around to the idea that we do live in a simulation, especially when considering our obsession with nostalgia in contemporary media and culture.

We simulate connection through social media, convincing ourselves that a quick scroll through someone’s curated feed is equivalent to picking up the phone for a brief chat. We simulate feeling informed and well-read through short bursts of news, little bite-sized paragraphs spoon-fed via newsletters or clips. We simulate political action by posting a black square or reposting a video about the Teamster strike while still consuming Amazon products we claim to hate but won’t do anything about “because of the convenience.” We simulate what life must have felt like “back then” to convince ourselves that “right now” doesn’t exist because to do otherwise would mean confronting something is wrong.

EVERYTHING OLD IS NEW AGAIN

It’s in this postmodern context that mass media becomes one of the few containers available to help us make sense of our modern society and our relation to each other.

Now that we have access to different forms of media across time, there is greater fluidity in identity and a desire to discover one’s “authentic self” in a world with seemingly infinite choices. If one “identifies” with a particular period or aesthetic, there are tools to more readily embody the style, mannerisms, and content that feels “true” to them. Think of Cottage Core, Dark Academia, or any number of content creators who promote “vintage style not vintage values.” Anyone can now latch on to an identity, even if they weren’t alive to experience it, a concept known as “displaced” nostalgia.

Our current definition of nostalgia focuses on making meaning of one’s present self by looking backward, either through one’s personal history or by consuming different products. I’ve spent the last few months mining the past, revisiting old photos, flipping through notebooks. During my trip to Texas this week, I even drove by old houses, parks, schools - all in an attempt to search for the girl I was to understand the woman I am now.

Earlier this month I revisited Jia Tolentino’s collection of essays, Trick Mirror. In the introduction, Tolentino talks about how she was unknowingly “leaving little breadcrumbs” for herself over the years. In many ways, I’d also like to think of my life over the last twenty years as little pieces I’ve unknowingly left for myself, all of which have culminated in this newsletter’s shift from personal essays to taking a broader look at how the internet informs past and current cultural trends.

This new direction in content represents something I’ve thought about and wanted to do for years, yet never seemed to muster the courage to do. However, if you’ve been following this newsletter for a while now, you’ll know that this was the year I decided to embody feeling limitless, to not contain my ambitions. Sharing my thoughts about the world around me feels like the truest expression of who I am and how I view the world around me.

In spending time looking backward, I can now finally see a way forward, a life where I am pursuing my creativity in a variety of different mediums and formats. I’m excited to continue exploring nostalgia, the internet, and postmodernist thoughts on culture with you all over the coming weeks and months.

xx kayla

Next Time: Mad Men and the Long Shadow of Boomer Culture

Including - oddly enough - philosophy, which was noted in a recent New Yorker profile on philosopher Laurie Paul.

FURTHER READING

Nostalgia: Sanctuary of Meaning (Janelle Wilson)

Simulacra and Simulation (Jean Baudrillard)

Postmodernism (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)