new year, old ways.

manifesting is just the latest in an attempt to have a sense of agency over our lives.

The end of the year often takes on a frenetic quality: holiday parties, purchasing last-minute gifts, reacquainting yourself with the suburban ennui that returns every time you spend more than 48 hours in your childhood bedroom. In between all of this, you must also somehow perfectly plan the next twelve months of your life.

Nothing technically separates today from last week. There isn’t a resolution judge issuing a stop work order preventing you from implementing changes in your life tomorrow or four months from now. Yet it’s hard to deny the seductive quality of something new, of telling yourself that this is when the changes you’ve always wanted to make will finally happen. Flipping the calendar over into a new year is a collective reset, a chance to develop amnesia about who we are and what we’re capable of. If we’re lucky, this life we’ve fashioned from our hopes and dreams on January 1 becomes fully actualized, no longer new but simply who we are. And if not, there’s always next year.

Planning for the year ahead now falls into a few broad categories for Millennial or Gen Z women. If you’re Type A, you’ll love Notion. For those wanting to take the pressure out of creating goals, gamify your resolutions and make a BINGO card. Want something a bit more woo-woo? Simply manifest.

Resolutions are not a new concept.

Babylonians rang in the new year during the spring equinox, a period signifying rebirth and renewal. Between planting crops and electing a new king, they also promised to repay debts and return borrowed farming equipment. The Romans would eventually adopt this practice, shifting the start of the year to after the winter equinox. Taking time to reflect was literally built into the first month of the year; Janus was a two-faced god who looked both forward to the future and backward at the past.

By the early nineteenth century, both new years and resolution had taken on their more modern place in American culture, appearing simultaneously in an 1813 article from a Boston newspaper in a moment of finger-wagging. The idea of turning to complete debauchery and “sin all the month of December” was just as relevant in early America as it is today when people turn to binge drinking or a bit of holiday overindulgence with the hopes that a new year will “wipe away all [your] former faults.”

Throughout much of history, resolutions often had this religious undertone. One of the earliest recorded modern resolutions comes from a Scottish noblewoman in the 1600s, who referred to her hopes for the year as “pledges” taken from Bible verses she wanted to embody or practice. Goals over the next several centuries, especially in America, would reflect the country’s Puritanical origins, with people hoping to do things like increase the amount of time they spent praying. There was also less of a focus on the individual and more on how to improve interpersonal interactions. Resolutions during the mid-twentieth century included a desire to improve one’s character, get involved around the house, and go to church more.

As the country has become more secular, resolutions began to change from spiritual and introspective to what we see today, which are more centered around individual fulfillment through either physical (lose weight; quit smoking) or material changes (earn more money). Our goals are now less about our connection to our community - religious or otherwise - and instead favor directly measurable outcomes. At a time when our society has begun to prioritize quantitative over qualitative experiences in everything from our technology to philosophy, it makes sense that our resolutions would also become distilled into metrics.

It’s much easier to sell you a pill promising clearer skin or a course on how to earn more money than it is to quantify “community involvement.”

Self-improvement is now a $13.4 billion industry.

Presenting an individualistic versus communal response to change has become the default because it’s simply much easier to sell a quick fix than it is to interrogate larger, systemic issues either in your personal life or in society. In this way, our quest for self-improvement becomes distilled into data and consumption in the form of everything from wearables to clothing.

Self-help isn’t new, but social media feels like the final boss, presenting an opportunity for influencers to hawk their courses, templates, and book recommendations, all with the promise that if they’ve achieved perfection, so can you. A better you is waiting around the corner, just as soon as you lose that weight and have clear skin and take your hot girl walk back to your dream apartment filled with the furniture and decor of your dreams because you deserve to become the best version of yourself - just as long as we can profit from it.

So you buy the Apple Watch to track your steps and fitness goals. You make weekly pilgrimages to Sephora in the hopes that this cleanser/mask/moisturizer is the key to pore-free, glassy skin. The best version of you means the best clothes, the best hair - even the best dumps, courtesy of detox pills and a Squatty Potty or bidet, which you can conveniently purchase directly from your favorite influencer through their TikTok shop.

“At the end of the day, there can always be a rebrand, a new fad, change in name, change in product - but the desire stays the same. If anything, we are the product, simply being sold back to us over and over again. You - but better.”

- Madisyn Brown

With all the meal prepping, working out, and gua shaing, there just aren’t enough hours in the day, but that’s okay. Organize your life on Notion (and purchase templates if you’re too busy to organize it yourself). Buy this book, watch this video. If your life isn’t organized down to the second, then there’s no one else but yourself to blame for not achieving your goals, which probably weren’t that great to begin with because they didn’t follow the 10-point plan outlined in the book you bought but didn’t finish.

In a world where we increasingly don’t have control, focusing on the individual is powerful, but it also increasingly feels like a series of boxes to check. Enter, manifestation, or “the art and quasi-spiritual science of willing things into existence through the power of desire, attention, and focus.”

Manifesting appears to offer an antidote to hustle and optimization culture.

As much as we like to think of ourselves as unique, the idea of manifesting has existed throughout history. In fact, it has its origins in the Renaissance.

Important thinkers of the time presented a radical concept in direct opposition to the Catholic Church, believing that “the defining characteristic of human beings was precisely that they are born to take the place of God.” But how does one become God? It wasn’t through getting ripped, but instead by an insatiable search for knowledge and science. Man’s purpose was “to fashion other natures, other courses, other orders” because we (humans) wouldn’t become fully actualized until we understood the world. Once we achieved this, humans would finally “manifest one’s desired purpose.”1

In the nineteenth century, this idea would get a slight rebrand through New Thought, a religious and metaphysical subculture started in Maine by a clockmaker/doctor/hypnotist (what a time to be alive) named Phineas Parkhurst Quimby. While treating patients, he observed that some progressed more than others. This led to the belief that people could cure their diseases by harnessing the power of the mind.

Quimby’s ideology would go on to inspire everything from the Christian Science movement to a wave of self-help books with titles like “Thought-Force in Business and Everyday Life” which argued that “the universe’s mysterious energies could be mastered by the human will.” Proto-mantras and affirmations from the turn of the nineteenth century included: “I am well. I am opulent. I have everything. I do right. I know.”

By the mid-twentieth century, New Thought and humanism would influence the engineers of Silicon Valley, who believed that the internet would help humans achieve their most actualized, fullest version of themselves. Online, we can craft whatever narrative we want, consuming content via algorithms that directly reinforce our worldview and thoughts in a way that is so niche it almost feels magical.

We have Oprah to thank for our more recent pop culture fascination with manifesting.

First released in 2006, the Secret popularized “the law of attraction” or how “like attracts like based on what we’re thinking and feeling.” Already popular amongst certain circles immediately after its release, it achieved mainstream success after Oprah dedicated two entire shows to talking about and promoting the book, which would go on to become one of the fastest-selling books of the decade.

In typical daytime fashion, the first episode highlights a few sad stories - a single mother with nearly $40,000 in credit card debt working a dead-end retail job; a couple stuck in a loveless marriage; a woman convinced she will never find love due to her weight - and presents how unlocking ‘the secret’ is supposed to resolve these issues.2 The advice given, both by Oprah but also by a panel on the show (which includes the creator of Chicken Soup for the Soul), wasn’t about getting a second job or suggesting couple’s therapy; it was all about “calling in” the outcome you want and not dwelling too much on the lack of money, love, or health you perceive you don’t have today.3

If you need a visual reminder of what you’re calling in, try a vision board. While they have existed conceptually for decades - first as mood boards that designers and other creatives would use to help clients envision a new space - the practice found its way to the corporate world by the early 2000s as a way for companies to visualize their goals and became widely popular following a reflection exercise in the Secret.

Vision boards in their current iteration are used to identify a future state (or vision) and are typically broken down into either five-year, annual, or quarterly versions. Putting together different images or words of what you hope to achieve is supposed to help with taking action through a process called “value-tagging,” which imprints important things onto your subconscious and filters out unnecessary information. Maybe you’ve made one yourself in a friend’s living room using that stack of magazines you keep meaning to recycle - or even paid to attend a visioning workshop. I can guarantee you know at least one person with a vision board (and if you don’t, I’m sharing mine for the year).

However, it’s not just enough to visualize the end result. While there’s nothing technically stopping you from putting a photo of a mansion or a dream vacation destination - one still needs to consider the hard work that goes into achieving results. That is, of course, unless you simply allow yourself to become delulu and trust that it’s all going to work out, no matter what.

By the pandemic, it felt like we were all manifesting - and maybe we were. Online searches for “manifesting” rose more than 600 percent during the first few months of the pandemic, which makes sense given how bleak and surreal spring 2020 felt. We were all seemingly “displaced, lost, and confused.” Telling yourself that all you need to do is have the ‘right’ mindset provides a certain level of comfort in an otherwise trying time where it feels like you have little control.

Newer trends point to a greater desire to abstract resolutions even further.

“Furries in the mainstream news. Girl Defined deconstructs or leaves the church. Death on the nine-month cruise. New Democratic nominee.”

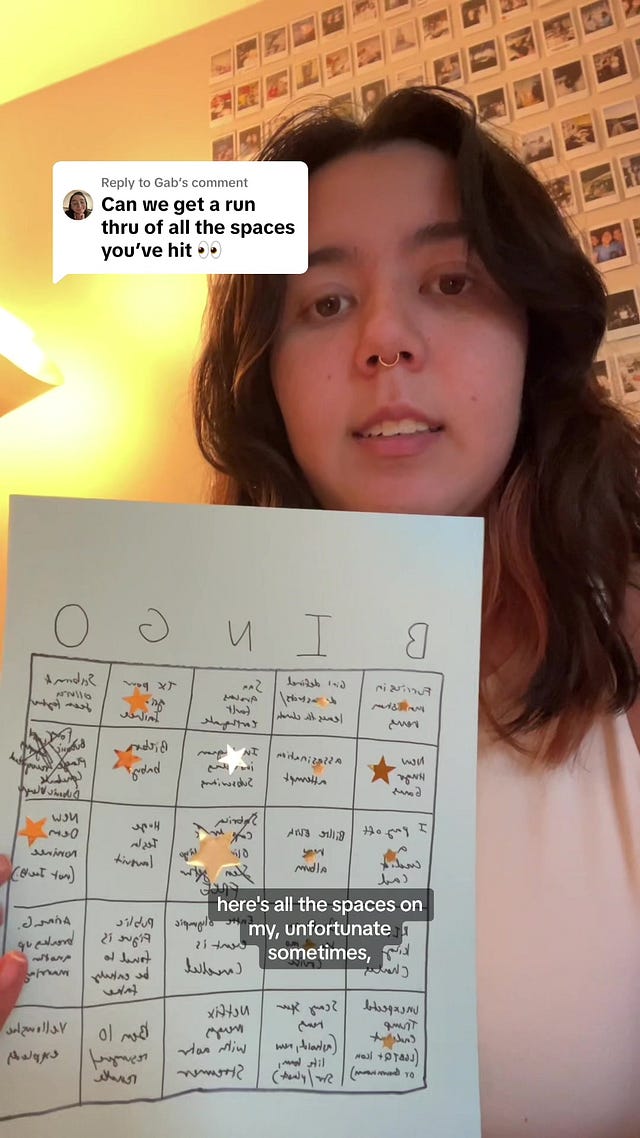

These were just some of the items on Laine’s 2024 BINGO card, which first made its way to my FYP over the summer. The premise was simple: think of a bunch of potential newsworthy or niche pop culture events at the beginning of the year, organize them in a 5x5 grid, and turn doom-scrolling the dumpster fire that is living in the 2020s into a fun, decidedly somewhat morbid game. By the end of the year, Laine had completed 18 out of 25 squares.

BINGO doesn’t always need to focus on trying to predict the news though. I first started seeing personal BINGO cards in early December as people began posting retrospectives reflecting on 2024 and preparing for 2025. Some use BINGO to either replace or supplement vision boards, others as a way to simplify their goals for the year ahead. Squares might include everything from more traditional goals, like learning a new skill, or serve as a reminder for planned trips and events that will happen throughout the year, such as graduating or taking a vacation.

Those wishing to both stick it to the man (who needs calendars?) while also remaining hyper-organized can choose to set goals not within a lame, 365-day format but instead adopt a 12-week year. The concept, taking the standard business practice of organizing the year into smaller quarters, rests on the idea that our brains crave a sense of urgency. If we can trick ourselves into thinking the end of the year is really three months from now, then apparently we’ll “get more done in twelve weeks than others do in one year.”

The start of the new year has always symbolized a period of change and personal growth. However - as with most things on the internet - the once private and seemingly innocuous act of jotting down a few resolutions or goals has become yet another example of how we seem more concerned with performing lifestyle changes to an audience rather than seeking out a new routine or habit just because. Of course, there’s also a quiet pleasure in knowing that none of this is new. Western culture has always looked for different ways to make us feel better about ourselves and provide a sense of agency - whether that’s New Thought or manifesting - while also commodifying our desire for betterment all at once.

And so the cycle continues, one hot girl walk and mindful manifestation ritual at a time.

For more on transhumanism, magic, and memes, check out Tara Isabella Burton's excellent essay.

Highly recommend giving the episode a full watch, not only to see how Oprah frames The Secret, but also for some serious 2000s nostalgia through some of the commercials that were included in the upload.

“If your life isn’t organized down to the second, then there’s no one else but yourself to blame for not achieving your goals, which probably weren’t that great to begin with because they didn’t follow the 10-point plan outlined in the book you bought but didn’t finish.” - loved this cutting sentence.